Anyone visiting the Gay Head Cliffs and Lighthouse can see how close the lighthouse is to the cliff-edge and how erosion threatens the Gay Head Lighthouse. Geological and engineering studies of the threatening situation were done in 2012. See below:

Gay Head Lighthouse Site Assessment

Aquinnah, Massachusetts

December 2012

Patrick Williams

Synopsis

Geological and engineering evaluations of landsliding at the site of the Gay Head Lighthouse were initiated in summer 2012. A survey (monitoring) array was established and a new survey of the bluff edge was completed. Historical data have been developed to show bluff retreat at an average rate of up to 1.8 feet per year during the period from 1870 to 2012. The general context of landsliding at the Gay Head Cliffs indicates that groundwater flows towards the cliffs, and likely accelerates sliding. Draining standing water (i.e. vernal pools and wetlands) to surface streams might diminish rates of land-sliding. For planning purposes, historical evidence indicates that moving the light to a location 180 feet farther from the bluff could be expected to protect the Gay Head Lighthouse for several generations.

Introduction

This report presents our progress in site evaluation, assembly of historical evidence, and establishment of survey monitoring for the Gay Head Lighthouse (GHL). The studies and activities summarized here are conducted by Patrick Williams (Williams Associates) and George Sourati (Sourati Engineering Group). The studies are directed to provide a sound basis to evaluate relocation alternatives for the GHL, particularly to support evaluation and monitoring of current and future site stability for the existing location and relocation alternatives. While we endeavor to provide and update the best available information on the present and future condition of lands surrounding the GHL, uncertainty and variability of natural processes are a given, and future influences cannot be known absolutely. Long-term average behavior presented here does not account for changing conditions of climate and weather events that during a given period may slow or speed mass wasting (landslide) processes in the immediate area of GHL.

Site context

Landslide activity is the primary agent of erosion at Gay Head Cliffs. The principal form of landsliding is “rotational slumping”, i.e. sliding surfaces are nearly flat in the lower portions of slides, but steepen gradually to nearly-vertical in the upper portion. Landsliding at Gay Head Cliffs is aided by several factors, principally high – steep topography, weakly consolidated sedimentary materials, and the action of waves removing material from the foot of the sliding mass. A substantial further effect, and probably the only effect with potential for human intervention, involves groundwater flow. Groundwater of the cliff area moves generally westward, towards the cliffs, moving through sand and fractures. Fluid pressure weakens shears, and adds moderately to the weight of the sliding material. If any one of these features (topography, low strength, wave erosion, the effect of water) was not present, the rate of sliding at the cliffs would likely be diminished.

The body of the Gay Head Cliffs is composed primarily of late Cretaceous (older than 65 million years) shallow-water marine deposits such as beach, estuary, marsh and lagoon. The materials are principally semi-consolidated clays and sands with some gravel. Equivalent deposits are present on the continental shelf from Maine to New Jersey. Sand intervals in the beds form local aquifers. The largest natural exposure of these ancient coastal deposits is that of Aquinnah’s Gay Head Cliffs. Claystone, sandstone, and (organic) lignite comprise the cliffs. Uplift, folding and faulting of the cliffs was caused by snowplow-like “ice-push” at the southern edge of recent glaciation. Hills and ridges of the larger up-island area were formed by the push, and many are cored by materials similar to those found at the cliffs.

Site evaluation

Landslide features of the lighthouse area were inspected on site and remotely using aerial photography and cross-section and measurement tools available within the mapping program Google Earth Pro (GEP). The distance from the lighthouse to bluff edge was measured in the field to be approximately 50 feet. The bluff edge is expressed by near-vertical drops of up to 10 feet, with subsequent steps and drops extending down slope. The bluff edges are scalloped by concave features, consistent with landslide head scarps[1].

Historical rate of bluff retreat

The original lighthouse tower at Gay Head was constructed in 1799. In 1844 contractor John Mayhew moved the structure 75 feet southward and away from the bluff edge. If the second location was approximately as far from the bluff edge as the original location, the 75-foot move and the 45-year time span indicate an approximation of the speed of bluff retreat: 1.7 feet/yr. Surprisingly this rate compares well with long-term rates evaluated from other evidence. Other survey data are referred to in Island planning documents, which might provide long-term retreat rates. The 1989 Martha’s Vineyard Commission (MVC) Decision of Critical Planning Concern (DCPC)[2] for the Gay Head Cliffs cites a general bluff retreat rate of 2.5 feet/yr for the period spanning 1845 to 1979 (MA Coast Survey, 1985; Kaye 1973). The subjects of both of these sources are coastline change, not bluff retreat, and we have thus far not reviewed the original materials to verify whether the 2.5 ft/yr rate actually refers to bluff retreat or in fact refers to coastline change.

![Figure 1. Aerial view and topographic cross section of bluff and northwest slide area. This image from Google Earth enables a general summary of landslide geometry. Height of bluff is approximately 130 feet. Distances from bluff edge to the back-beach ranges[CK1] from 350 to 400 feet. Average slope down the landslide area varies from 28% to 37% (15° to 20°), but locally slopes are much steeper. Steps in the profile suggest at least three major slide blocks. Vegetation patterns define individual slide masses in several cases, and where they are well-defined indicate the style of sliding. Most patches of vegetation on the slope are displaced from the original bluff surface. Areas bare of vegetation reflect scars from separation of slide blocks, and areas with erosion rates too high for vegetation to be established. Image courtesy Patrick Williams](http://gayheadlight.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/topaerial.png)

Figure 1. Aerial view and topographic cross section of bluff and northwest slide area. This image from Google Earth enables a general summary of landslide geometry. Height of bluff is approximately 130 feet. Distances from bluff edge to the back-beach ranges[CK1] from 350 to 400 feet. Average slope down the landslide area varies from 28% to 37% (15° to 20°), but locally slopes are much steeper. Steps in the profile suggest at least three major slide blocks. Vegetation patterns define individual slide masses in several cases, and where they are well-defined indicate the style of sliding. Most patches of vegetation on the slope are displaced from the original bluff surface. Areas bare of vegetation reflect scars from separation of slide blocks, and areas with erosion rates too high for vegetation to be established. Image courtesy Patrick Williams

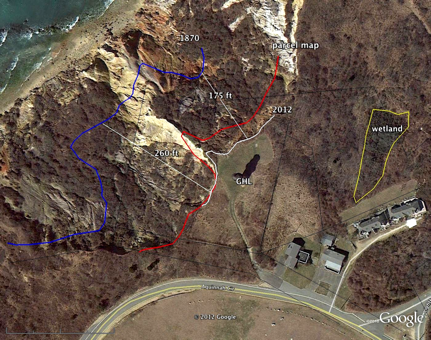

Figure 2. Overlay of 1870 map (lot numbers and bounds on the 1870 map are hand drawn) and modern parcel map for lighthouse area. Note bluff edge is well delineated in 1870, and “U.S.L.H.S.” parcel is a square approx. 300 feet on each side. The modern parcel map overlays very well on the 1870 map, particularly for lots 21, 22, and 23. Note 150-300 ft of bluff retreat in the interval between the two maps.

Survey of lighthouse grounds

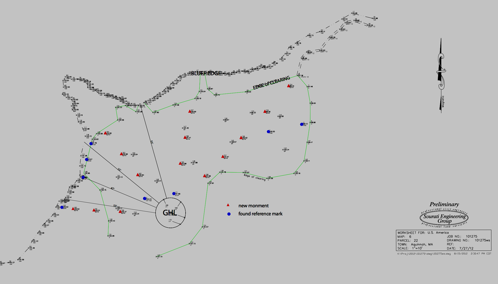

To establish present location of the bluff edge and to monitor future changes to the site as new ground failure encroaches on the lighthouse, 167 survey points were recorded between the light[CK4] and the bluff by Sourati Engineering Group (SEG) in August 2012 (Figure 3). Fourteen temporary monuments were placed, and 8 “permanent” features such as fence posts, existing monuments and found features were documented. The bluff edge was defined by nearly 100 laser survey measurements. Additional features located are the edge of the lighthouse clearing and the location of trails. Future surveys will encompass local permanent bounds markers to tie the array and surveyed features to the town plat map and to parcel surveys. Note that the closest distance [CK5]to the bluff edge at the time of 2012 survey are 47’, 53’, 55’ and 55’.

Rate of bluff retreat

The 2012 SEG bluff-edge survey has been compared to the 1870 bluff edge by hand fitting of the two maps with a Google Earth template (Figure 4). Reference marks for the fitting include house locations, fence lines,surveyed references (trails, clearing, fence, and the light itself). With these aids, the 1870 bluff edge is believed to be located within an accuracy of about 10 feet, and the 2012 survey to within 5 feet (in the GEP visualization). In representative locations the bluff has suffered retreat of 175 feet and 260 feet. This indicates an average rate of bluff retreat of up to 1.8 feet-per-year during the latest 142 year [CK6]period.

Figure 3. 2012 survey of immediate GHL grounds by Sourati Engineering Group. Note placed monuments are denoted by red triangles. Found reference marks are marked with blue circles. The upper left (northwest) boundary is the bluff edge. Edge of clearing is marked with a green line within the central area of the survey. Note distances to bluff edge are 47’, 53’, 55’ and 55’.

Figure 4. Summary of a 142 year record of bluff retreat at Gay Head Light[CK7]. Property bounds shown are those from the 1870 Aquinnah town map. Blue line is the bluff edge as mapped in 1870. Red is from the current town map. White is from the 2012 survey (this report). Retreat of 260 feet in 142 years indicates an average rate of bluff retreat of 1.8 feet/year. Bluff retreat of 175 feet in 142 years indicates retreat at 1.2 feet/year.

This study is planned to continue through December 2014. The scope of the current study includes repeating and evaluating the land survey annually, continuing to gather and evaluate historical documentation, and applying existing airborne laser scanning data to map landslide structures to better evaluate the rate and style of mass wasting. Each of these tasks will improve and support the [CK8]preliminary results summarized here.

Significant additional tasks for consideration include providing more detailed prognosis and site engineering for candidate relocation sites, and developing a proposal for groundwater mitigation.

References

Kaye, C. A., Map Showing Changes in Shoreline of Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts, During the Past 200 Years, with text, USGS Miscellaneous Field Studies Map: MF-534 Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey.*

Long, J. P., The Gay Head Landslides, Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts, Causes and Remedies, Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation, University of Connecticut, 1971.

Martha’s Vineyard Commission: Decision of the MVC Designating Gay Head Cliffs as a District of Critical Planning Concern MAY 4 1989.http://www.mvcommission.org/doc.php/DCPC%20Decision%20Gay%20Head%20Cliffs.pdf?id=292(7).

Massachusetts Shoreline Change Project, Executive Office of Environmental Affairs, Massachusetts Coastal Zone Management Office, Shoreline Change Map, University of Maryland Coastal Mapping Group, 1985. *

Richardson, J. , The Gay Head Lighthouse and its geologic future (Houston, we have a problem). Report to Martha’s Vineyard Museum, May 10, 2010.

Van Westen , C. J., Geo-Information tools for Landslide Risk Assessment. An overview of recent developments, International Institute for Geo-Information Science and Earth Observation (ITC), Enschede, The Netherlands.

[1] A head scarp represents a fracture produced by the calving away of a slide block from an intact body of earth.

[2] Martha’s Vineyard Commission: Decision of the MVC Designating Gay Head Cliffs as a District of Critical Planning Concern MAY 4 1989. http://www.mvcommission.org/doc.php/DCPC%20Decision%20Gay%20Head%20Cliffs.pdf?id=292

“A further study of the District (7) documents that seepage facilitates landslides along the west-facing cliff, as the bulk of groundwater seepage travels westward. The landslides of the Cliff area have a yearly cyclic rhythm with a small displacement during summer and early fall, very rapid rate during winter and early spring, and a slowing period in late spring. A correlation exists between rates of slide movement and infiltration. The study concludes that groundwater seepage is probably a major cause for landsliding.

Cliff erosion averaged 2.5 feet per year from 1845-1979 (8). This erosion results from landsliding, rainwash and wave erosion, with landsliding described as the most important process contributing to the erosion. Landsliding “begins by a vertical crack forming parallel to the Cliff and back from the edge by distances as great as 100 feet but generally less than 20 feet”. The strip of land bounded by the crack begins to drop vertically as much as 15 feet in a few months, eventually pushing masses of clay onto the beach and vulnerable to wave action (9).”

* (original material not yet located).